A good day at the museum is rediscovering the history of a specimen or artifact that has lost its association with the record that tells us who, where and why it has come to the museum. Sometimes it takes archival research to do this and sometimes it's purely serendipitous.

This weekend I discovered a copy of "

Intracranial Tumors Among the Insane (1902) by Dr. I. W. Blackburn

in a

used bookstore in Gaithersburg, MD. Dr. Blackburn was the former pathologist for

St. Elizabeth's Hospital in Washington, D.C. He performed hundreds maybe thousands of

autopsies on patients who died at the hospital. While browsing through the book I noticed a photo of very unique calvarium (top of the skull). The specimen had two rare conditions;

scaphocephaly and

hyperostosis frontalis interna. The bone looked strangely familiar.

In the

Anatomical Division of NMHM we have such a specimen. It was listed as coming to the museum from an early exchange with the Smithsonian National Museum and not attributed to St. Elizabeth's at all. I bought the book for $15 and lo and behold when I brought it back to the museum our specimen was the same one in the book. It was attributed to a 65 year old black female patient at St. Es. The existing record was based on a bygone curatorial staff member using the wrong

numbering system to describe the specimen. There have been several systems in place at the museum at various times which causes a lot of confusion for us today.

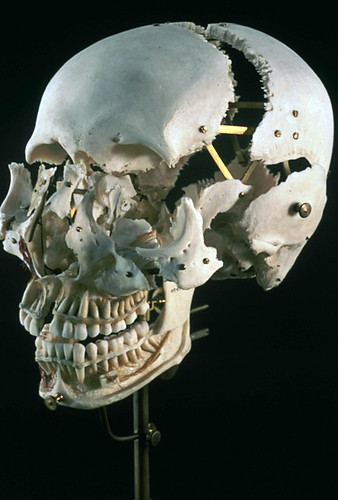

Here is a recent photo of the specimen. In addition to the pathological conditions there are also consistencies among the size and shape of the exposed frontal sinus, the etchings of the meningeal vessels, the contours of the thickened frontal bone and the two small bony exostoses in the center just left of the midline. The front of the skull is oriented to the right.

The specimen's history is now restored. Additionally, four other calvaria in the collection with no known history have similarly composed autopsy numbers written on the bones. All are now believed to be from St. Elizabeth's with further research pending. These specimens have very early accession numbers which means that they arrived at the museum around 1917-1918 when the Army Medical Museum was busy attending to the medical needs of World War I. It is not clear when the original error was made, but it likely extends back several decades. The specimens themselves are from the late 19th century autopsies.

In the photo below you can see the scaphocephalic calvarium (left) next to a normal one (right). Notice that the normal one on the right has a jagged line called the

sagittal suture (front to back) which the one on the left lacks. Sutures are where the bones of the cranium grow and expand. In scaphocephaly the sagittal suture fuses prematurely and the

coronal suture continues to grow which gives the unique elongated shape you see here. The one on the left is darker due to over 100 years of dust and dirt adhering to oils that remained in the bone. Since bone is porous, it can absorb materials from the environment which effect its color. The one on the right was cleaned using chemicals that removed much of the oils and was stored in a relatively cleaner environment.