An unofficial blog about the National Museum of Health and Medicine (nee the Army Medical Museum) in Silver Spring, MD. Visit for news about the museum, new projects, musing on the history of medicine and neat pictures.

Thursday, March 31, 2011

Letter of the Day: March 31

Surgeon General's Office

U.S. Army Medical Museum and Library

Corner 7th and B Streets SW

Washington, March 31, 1903

Dr. John Moras

140 Eighty-second St., West

New York, N.Y.

Dear Sir:

Your letter of the 29th inst. to Major Walter Reed, was received at this Museum to-day, and I regret to inform you that Dr. Reed died of appendicitis on November 23, 1902. I enclose a copy of the memorial pamphlet issued by the Medical Association of the District of Columbia.

The investigations of the American Yellow Fever Commission, seven articles in all, were published in different Journals, and I am only able to send you reprints of four of these. The other three articles appear as follows:

"Experimental Yellow Fever" in American Medicine, Phila., July 6, 1901.

"The Etiology of Yellow Fever. A supplemental Note" in American Medicine. February 22, 1902.

"Recent Researches concerning the Etiology, Propagation and Prevention of Yellow Fever by the U.S. Army Commission" in Journal of Hygiene, Vol. II No. 2, 1st April, 1902.

Very respectfully,

James Carroll

1st Lieut. Asst. Surgeon, U.S. Army,

Asst. Curator., A.M.M.

Thursday, February 17, 2011

Yellow Fever and Walter Reed

Yellow Fever and Walter Reed

Yellow fever is caused by a virus transmitted by a mosquito. This disease has menaced communities since before the founding of the United States. Yellow fever was first described by Joam Ferreyra Da Rosa in 1694. The origin of the term "yellow fever", however, is obscure. Some feel the name reflects the symptoms since the virus destroys liver cells and causes jaundice which is a yellowing of the skin and eyes. Others feel that the name refers to the yellow quarantine flag flown by ships carrying the disease, especially since the fever apparently travelled from Africa on slave ships which were notorious carriers of the fever.

Yellow fever has a wide variety of symptoms including headaches, backaches, nausea and fever. The most disturbing symptom is bloody vomiting which gave the disease the vivid name of "the black vomit". The disease has a fatality rate between 10 and 15% but is less virulent in children. Currently, the disease is incurable and attentive nursing and rest are the only treatments.

Walter Reed was born in Virginia in 1851. In 1869, Reed graduated from the University of Virginia with a degree in medicine and studied at Bellevue Medical Hospital in New York. He joined the Army Medical Corps in 1875 and spent most of the next two decades at frontier posts. In 1893, Reed began serving as curator of the Army Medical Museum and professor of bacteriology and clinical microscopy at the Army Medical School. As part of the Surgeon General's Office staff in Washington, Reed was assigned to investigate typhoid fever in 1898 and then yellow fever a year later.

Reed was the first man to prove the mechanics of infection of yellow fever. Prior to his work, several novel ideas had been considered.

For instance, Benjamin Rush, the noted Philadelphia physician, believed the disease was caused by rotten coffee. Others held that "miasmas" or bad airs were the cause. However, throughout the century, glimpses of the true means of transmission had been noted. In 188 Dr. Josiah C. Nott of Alabama suggested that mosquitoes might be the vector or carrier of the disease. Carlos Juan Finlay of Cuba strongly advanced this idea although current theory held that "fomites" or household articles were somehow infected with the disease.

In 1899 during the wake of the Spanish-American War, Reed headed a team investigating the cause of yellow fever. The team, composed of Dr. James Carroll (also of the Army Medical Museum), Dr. Aristides Agramonte and Dr. Jesse Lazear, convened at Columbia Barracks near Havana, Cuba. Their first accomplishment was to quickly rule out a recently-proposed bacterial theory. Then, using volunteers, the team tested the fomite theory with articles fouled with the effusions from yellow fever victims. This theory, too, was proven wrong. After a prison outbreak when one prisoner was infected and died but the eight other prisoners were not infected, researchers could not suggest a method of transmission other than mosquitoes. Finlay had provided mosquitoes for testing and Dr. Lazear began experiments with them. By having a mosquito bite them, Lazear successfully infected Dr. Carroll and a volunteer soldier named Dean in August. Lazear may have been testing his theory on himself for he was infected and died on September 25, 1900. Lazear's notebooks enabled Reed to study the data Lazear compiled. Reed realized that the Aedes aegypti mosquito carried yellow fever but only under certain conditions. The mosquito must bite a yellow fever victim during the first three days of an attack, incubate the virus in its body for at least twelve days and then bite another person to pass on the disease. This discovery enabled the United States to essentially eradicate yellow fever within its borders after one last epidemic in New Orleans in 1905. The disease proved easy to conquer because the Aedes aegypti mosquito is an urban mosquito and breeds only in small pools of stagnant water such as fish ponds or even flower jars. Yellow fever is still prevalent in tropical climes due to both a different mosquito vector, the Haemagogus spegazzinii and the fact that jungle yellow fever, as it is occasionally known, can live in monkeys as well as human hosts.

Object List:

Two Reed medals (M-900 00682, ASTM medal; M-900 00683, Congressional medal) Text: Medals awarded to Walter Reed for his work on yellow fever by Congress and the American Society of Tropical Medicine. M-900 00683; M-900 00682.

Photo of Reed at 25 (NCP 876 Text: Reed at age 25. NCP #876

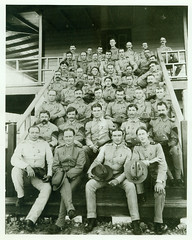

Sontag volunteers photo. Text: Soldiers who volunteered for yellow fever experiments. Sontag Collection.

Reed microscope (M-030 00420) Text: Microscope used by Reed. M-030 00420.

Mosquito drawing

Sunday, February 6, 2011

Letter of the Day: February 6

Curatorial Records: Numbered Correspondence 09190

To 1st Lieut. James Carroll,

Assistant Surgeon, U.S.A.,

Washington, D.C., for remark

S. G. O.

Feb. 5, 1906

2d Indorsement [sic],

Surgeon General’s Office,

Army medical Museum

February 6, 1906

Respectfully returned to the SURGEON GENERAL, U.S. ARMY.

This matter was broached to me on January 2d at New Orleans, and I then expressed my willingness to come, provided it would be agreeable to the Surgeon General.

I am quite willing to prepare an address for the occasion, because an opportunity will be afforded to present the facts and arguments in a forcible manner where they will do the greatest good. The future safety of the United States from yellow fever depends largely upon the readiness of the physicians of Louisiana to recognize and declare the disease upon its first appearance among them. The importance of the subject to the Army and to the country at large is my reason for consenting to participate.

James Carroll

1st Lieut., Asst. Surgeon, U.S.A.

Curator.

Monday, July 26, 2010

Who is Walter Reed?

Walter Reed was born in Virginia in 1851. In 1869, after a year of medical school, Reed graduated from the University of Virginia with a degree in medicine. He then studied at Bellevue Medical Hospital in New York. He joined the Army Medical Corps in 1875 and spent most of the next two decades at frontier posts, but did post-graduate education at Johns Hopkins and other places. In 1893, Reed began serving as curator of the Army Medical Museum and professor of bacteriology and clinical microscopy at the Army Medical School. As part of the Surgeon General's Office staff in Washington, Reed was assigned to investigate typhoid fever in 1898 and then yellow fever a year later.

Reed spent the war studying typhoid fever. In 1899 during the wake of the Spanish-American War, Reed and Dr. James Carroll (also of the Army Medical Museum) investigated the bacteria thought to cause the disease and concluded that it did not. In May 1900, Reed headed the Yellow Fever Board, investigating the cause of the fever. The team, including Reed and Carroll also included Dr. Jesse Lazear and Cuban-born probably-immune Dr. Aristides Agramonte. The men who all knew each other convened at Columbia Barracks near Havana, Cuba. Their first accomplishment was to again rule out the recently-proposed bacterial theory. After a prison outbreak when one prisoner was infected and died but the eight other prisoners were not infected, Reed suggested a method of transmission by mosquitoes, which were already known to transmit malaria. Finlay was contacted and provided mosquitoes for testing and Dr. Lazear, who had previously worked with mosquitoes, began experiments in a lab at the Barracks with them while Reed returned to Washington to finish the Typhoid Board's report. Since no animals were known to get the fever, the Yellow Fever Board concluded that the ethical experiment would be to try to infect themselves. By having a mosquito bite them, Lazear successfully infected Dr. Carroll and a volunteer soldier named Pvt. William Dean in August. Lazear though may also have been testing himself for he was infected and died on September 25, 1900. He had reported being bitten by accident in Havana, but his notes implied he might have experimented on himself; Reed was not sure if Lazear was infected accidentally or purposefully, but accepted the accidental theory. Lazear's notebooks enabled Reed to study the data Lazear compiled when he returned from the States. Transmission by mosquito was obvious to the Board at that point and Reed reported that they were the cause in October - after 5 months of work, not a year as stated in the movie. The Washington Post called the hypothesis "the silliest beyond compare," but in November, Camp Lazear was established as a quarantine site to prove the theory beyond a doubt. Fourteen American soldiers volunteered and recent Spanish immigrants were hired using the first "informed consent" form. Private John Kissinger was the first to get the fever, and Charles Sontag, the last. No one in the experiment died, Spanish or American. Congress eventually authorized gold medals for the American volunteers. Using volunteers, the team also tested the fomite theory with articles fouled with the effusions from yellow fever victims including the dead men's clothes (although they were allowed to eat outside). This theory was proven wrong - "burst like a bubble" in Reed's words.

Reed realized that the Aedes aegypti mosquito (which has been renamed three times) carried yellow fever but only under certain conditions. The female mosquito must bite a yellow fever victim during the first three days of an attack, incubate the virus in its body for at least twelve days and then bite another person to pass on the disease. Reed's team was the first to prove the mechanics of infection of yellow fever. Since there was no cure or vaccine, soldiers continued to die from the disease, but Gorgas' mosquito control efforts meant by the summer of 1901, Havana was free of yellow fever. This discovery enabled the United States to essentially eradicate yellow fever within its borders after one last epidemic in New Orleans in 1905. In Panama, William Gorgas was able to suppress the disease so the Panama Canal could be built, although he was able to use methods such as oiling water so the mosquitoes suffocated. The disease proved easy to conquer because the Aedes aegypti mosquito is an urban mosquito and breeds only in small pools of stagnant water such as fish ponds or even flower jars. Although a vaccine was developed in the 1930s, yellow fever is still prevalent in tropical climes due to both a different mosquito vector and the fact that jungle yellow fever, as it is occasionally known, can live in monkeys as well as human hosts.

Reed died in 1902, of appendicitis, at Washington Barracks hospital, now on Fort McNair in the District. The hospital named in his honor opened in 1909, and the Museum he headed is open to the public on its grounds until the hospital closes and the Museum moves in 2011.

Monday, June 7, 2010

Letter of the Day: June 7 (1 of 2) - Cuba! Yellow Fever! Sea Sickness!

Curatorial Records: Numbered Correspondence 4638

War Department,

Office of the Surgeon General,

Army Medical Museum and Library,

Washington,

June 7, 1900

Lt. Col. Francis B. Jones,

Quartermaster’s Department, U.S.A.

Army Building, 39 Whitehall St.

New York, N.Y.

Sir:

Per Special Orders No. 122, Par. 33, A.G.O. May 24, 1900, Actg. Asst. Surgeon James Carroll and I are ordered to proceed from New York City to Havana, Cuba. I have this day been informed by Col. Bird, of your Department, that the transports Crook and Sedgwick will probably sail from New York for Havana about June 20th, and I, therefore, request that you will kindly reserve accommodations for Dr. Carroll and myself on one of these vessels. As both of us suffer very much from sea-sickness we would be glad to give state rooms amidships, if possible, and on the transport that is considered the steadiest sea-going boat.

Very respectfully,

Walter Reed

Major & Surgeon,

U.S. Army

Tuesday, May 25, 2010

Letter of the Day: May 25 - yellow fever

War Department,

Office of the Surgeon General,

Army Medical Museum and Library,

Washington,

May 25, 1900

Dr. Jesse Lazaer

Actg. Asst. Surgeon, U.S.A.

Camp Columbia

Quemados, Cuba

My Dear Doctor:

An order issued yesterday from the War Department, calls for a Board of Medical Officers for the investigation of acute infectious diseases occurring on the Island of Cuba. The Board consists of Carroll, yourself, Agramonte and the writer. It will be our duty, under verbal instructions from the Surgeon General, to continue the investigation of the causation of yellow fever. The Surgeon General expects us to make use of the laboratory at Military Hospital No. 1, used by Agramonte, and your laboratory at Camp Columbia.

According to the present plan, Carroll and I will be quartered at Camp Columbia. We propose to bring with us our microscopes and such other apparatus as may be necessary for bacteriological and pathological work. If, therefore, you will promptly send me a list of apparatus on hand in your laboratory, it will serve as a very great help in enabling us to decide as to what we should include in our equipment. Any suggestions that you have to make will be much appreciated.

Carroll and I expect to leave New York, on transport, between the 15th and 20th of June, and are looking forward, with much pleasure, to our association with you and Agramonte in this interesting work. As far as I can see we have a year or two of work before us. Trusting that you will let me hear from you promptly, and with best wishes,

Sincerely yours,

Walter Reed

Major & Surgeon,

U.S. Army

Tuesday, November 3, 2009

Have you ever heard of the Isthmian Canal?

This first one is a lovely hand-tinted lantern slide of Spanish laborers.

This second one is a chart (table?) showing a marked decrease in fatalities from various diseases, supposedly when sanitary measures were put in place- such as covering food, digging drainage ditches, oiling still bodies of water, etc. Note the Americans giving themselves a big old pat on the back.

Wednesday, October 7, 2009

More good stuff from the Registry

James Carroll was a Major in the Army who worked with Walter Reed on his yellow fever research. He volunteered to be bitten by a mosquito that had previously bitten three others who had yellow fever. He contracted the disease and several years later died of cardiac disease that was attributed to his bout of yellow fever.

Here's a letter from the President of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, petitioning a Congressman to grant a special pension to Carroll's widow.

Page 1

Page 2

And here is the Congressman's reply.

Maybe I'm missing something, but I thought being a Major in the Army meant you were in military service to your country.

Friday, May 22, 2009

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Here's what I found in one of them:

Scene from the Epidemic of Yellow Fever in Cadiz,

Théodore Géricault,

ca. 1819