A museum in Ford's Theatre is mentioned in passing in this article "The History Will Linger At Remade Ford's Theatre," By Michael E. Ruane, Washington Post Staff Writer, Friday, August 15, 2008; Page A01.

Ruane wrote, "The government bought the theater from Ford and used it over the years as a museum and as an office and storage building."

Well, that was the Army Medical Museum which was there for almost two decades, before it moved to a new bulding on the Mall (which was knocked down in 1968 for the Hirschorn). I wrote about the Museum there in Washington History (available from the Washington Historical Society) last year. Here's some relevant paragraphs edited down somewhat:

After President Lincoln's assassination in 1865, the federal government purchased and renovated the notorious Ford's Theatre to house the museum, the Surgeon General's Library, and the more than 16,000 bound volumes of the Records and Pension Division of the Surgeon General's Office. The move to Ford's Theatre in December 1866 permitted the museum to expand its collecting to include Native American weapons and “specimens of comparative anatomy.” Now the museum, with its larger exhibit space and broader scope, would become a well-known Washington-area landmark.

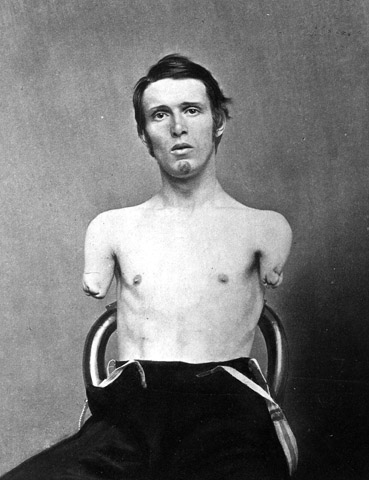

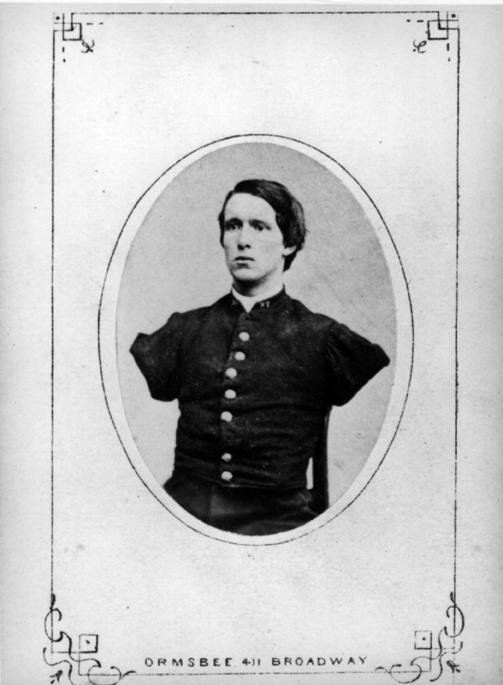

The museum had no difficulty attracting the public. Medical specimens, including many anomalies and curiosities, fascinated both lay and professional visitors alike. No doubt part of the fascination lay in the innate morbid curiosity of seeing human remains usually available in circus side-shows, but the Civil War had just ended, and the displays of specimens from maimed soldiers of both sides led visitors to see the museum as an unintentional national memorial. The glass cases of specimens were flanked by flags and standards of ambulances corps as well as Union and Confederate swords and sabers. While the displays were systematic, rather than artistic, they were nonetheless alluring, especially for thrill-seekers. A reporter for the popular Appleton’s Journal captured the atmosphere:

It is, indeed, not such a collection as the timid would care to visit at midnight, and alone. Fancy the pale moonlight lighting up with a bluish tinge, the blanched skeletons and grinning skulls — the same moon that saw, in many a case, the death-blow given, or the bullet pierce. The thought is not a comforting one, and those fancies would not be calculated, at such a time, to inspire courage. But in broad daylight, with the sun shining outside, and brightening up, with its tinge of life and activity, the tessellated floor, with the noise and traffic of the street outside, and the hum and murmur of numerous clerks and attendants inside, even those of timid proclivities do not then hesitate to inspect closely and with curiosity the objects which, twelve hours later, when the building is dark and deserted, they would scarce care to approach.

Opened to the public on April 16, 1867, the museum drew around 6,000 visitors by the end of the year. “It cannot fail to be one of the most absorbing spots on earth to the student of surgery or medicine,” opined guidebook author Mary Clemmer Ames in 1874, “but to the unscientific mind, especially to one still aching with the memories of war, it must remain a museum of horrors. . . . No! the Museum is a very interesting, but can never be a popular place to visit." In spite, or because, of Ames's concerns, by 1874, the number of visitors sometimes reached more than 2,600 per month, even the museum was only open from 10 am to 3 pm on weekdays, and on Saturday from 10 am to 2 pm. As early as 1866, the museum was well-known enough to be mentioned in Atlantic Monthly. In Dr. S. Weir Mitchell's fictional story, "The Case of George Dedlow," the hero, who lost both legs due to the war, was contacted by spirits during a séance. The spirits proved to be his amputated limbs, preserved in the Medical Museum: "A strange sense of wonder filled [Dedlow], and, to the amazement of every one, I arose, and, staggering a little, walked across the room on limbs invisible to them or me. It was no wonder I staggered, for, as I briefly reflected, my legs had been nine months in the strongest alcohol." Undoubtedly, readers of the story would have wished to visit the museum to look for the imaginary Dedlow's limbs.

As early as 1880, the Ford's Theatre building was proving inadequate for the expanding museum and library. In fact one exterior wall as falling away, and eventually the interior floors collapsed after the museum had moved out. In 1881 the museum attracted 40,000 visitors, while in 1888, the library had 5,000 readers. In his annual message to Congress, President Rutherford Hayes asked for an appropriation to replace the building. “The collection of books, specimens, and records constituting the Army Medical Museum and Library are of national importance. . . ,” Hayes wrote. “Their destruction would be an irreparable loss not only to the United States but to the world.”

Some congressmen opposed the idea of a new building, suggesting instead that the Army's medical records merge with the Pension Bureau's in their new building (now the National Building Museum), or amalgam the library with the Library of Congress and the museum with the Smithsonian Institution. Representative Clarkson Potter of New York objected on emotional grounds and opposed funding the museum and “preserving the relics and bones or wounds caused by the war at any place in our capital,” wishing instead that "they were all buried and covered all over with green grass and hidden from sight forever." On the other side, the more forward-thinking Representative Theodore Lyman of Massachusetts envisioned an institution something like today’s National Institutes of Health and "discern[ed] a hope that , , , germs may be used for inoculation and may protect us from . . . diseases, just as vaccination protects against smallpox.” Lyman deemed the museum’s studies “essential to the welfare of our people,” and the library “now the first in the world, and whose not less admirable collection of military pathology, are placed at the disposal of all investigators.”

The full article, "The Rise and Fall of the Army Medical Museum," has much more information in it of course.

To show that nothing really changes, we're currently scheduled to move off of Walter Reed Army Medical Center's DC campus due to the BRAC closure of the base, but no new home has been designated for us.

Ruane also wrote, "On the morning of June 9, 1893, the building was packed with 500 government clerks, occupying several floors of jury-rigged office space, when the interior collapsed, according to a Washington Post account the next day. Scores were killed and injured, and the theater's already altered interior was destroyed."

The space wasn't jury-rigged - actually it was built of cast iron, fireproof construction, but the space wasn't strong enough for all the tons of pension records that were being stored there.